Women artists at work: nineteenth-century examples

Recent years have seen an increased interest in the too often forgotten role of women in art history. Women have received renewed attention for their achievements as collectors, patrons, historians, curators, museum directors, and, obviously, artists. Since starting her collection, Katrin Bellinger actively sought out and acquired interesting representations of women artists at work. For the most part obscure, these examples, ranging from the early modern period to the present, not only enrich our understanding of the topic of the artist at work but also constitute a developing area of study on their own.

My personal fascination with the subject of women artists is an advantage when researching and seeking to expand our holdings. As well as tracing little-known works I also keep up to speed with the new findings in the field. In the past year alone, several exhibitions and conferences were devoted to the topic [1]. Of particular interest was the Christie’s Education Conference entitled Celebrating Female Agency in the Arts (New York, 26-27 June 2018) where the activities of female artists, across ages and countries, were integrated in broader networks of female patronage and curatorship, which made for a truly fascinating event. Here, I want to consider just a couple of examples from the collection to shine light on this intriguing subject.

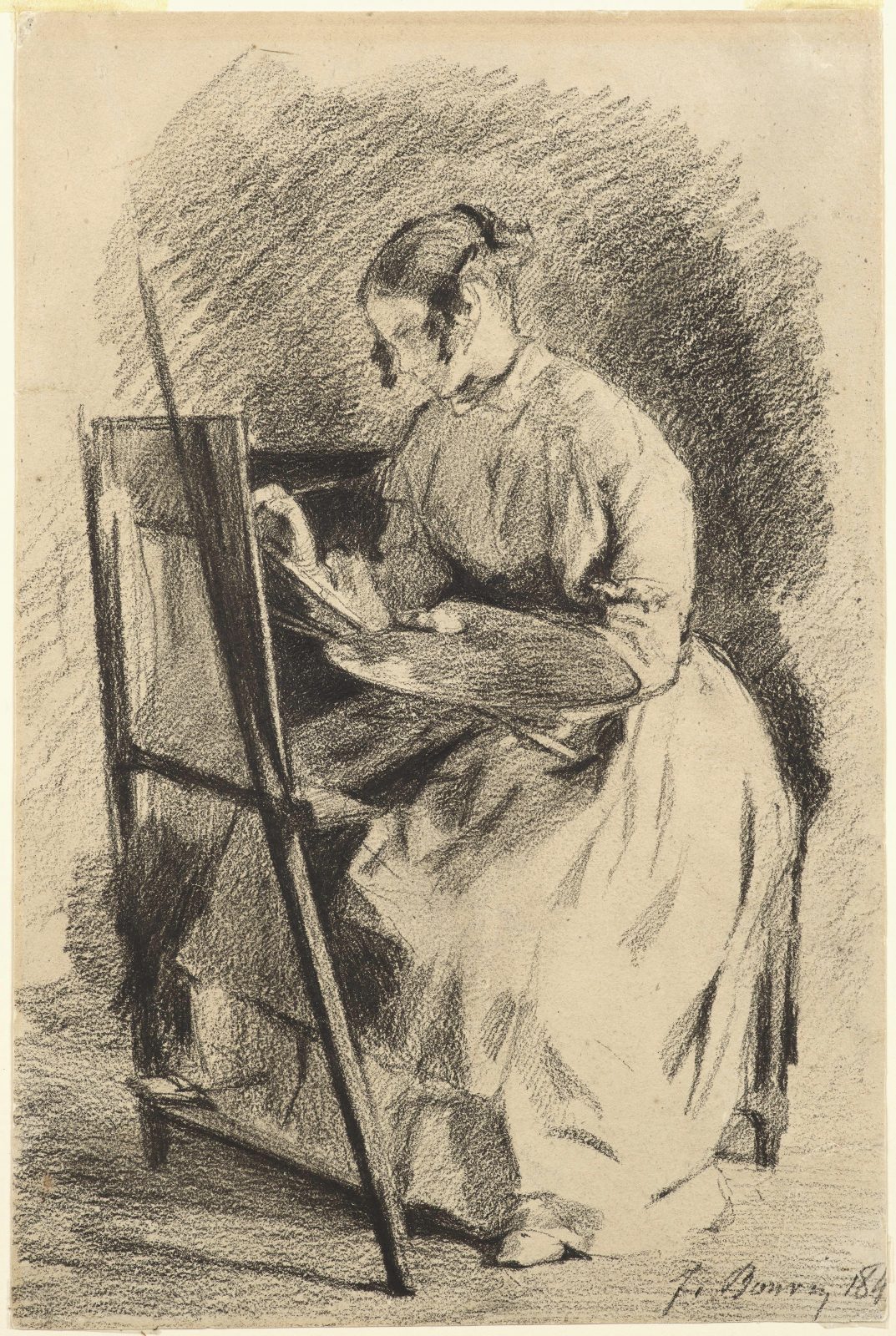

A recent addition to the collection is a portrait of a woman painter at her easel (fig. 1) by the French realist artist François Bonvin (1817-1887). Executed in 1848 it portrays Sophie Unternährer, sister of Bonvin’s mistress at the time, Eléonore. [2] Long considered lost, the painting was recently rediscovered, giving us the rare and exciting opportunity to reunite it with one of its preparatory drawings, in black chalk (fig. 2), already in the collection. The painting exemplifies Bonvin’s vigorous style combined with a restrained colour palette. Sophie in her grey dress appears as a presence created by light. A few touches of white serve to highlight her hand with the brush, her jaw and neck, and her dress’s collar. Flicks of light also define the objects surrounding her. The dramatic illumination and the rendering of the interior in the oil attest to Bonvin’s familiarity with the works of the Dutch Old Masters that he studied at the Louvre. Although little is known today of Sophie’s own style, we do know that, with her sister and Bonvin, she belonged to a circle of friends called ‘groupe de la bohème’. [3] Notable members were also Gustave Courbet and the writer and art critic Jules François Felix Fleury-Husson, called Champfleury, the early promoter of the realist movement.

Fortunately, many fascinating representations of women artists realised by women do exist, whether in the form of self-portraits or as depictions of their fellow art school trainees or peers. Such images often defy traditional expectations on the training and professional opportunities available to women artists. While Sophie Unternährer may have received an informal artistic training, in the second half of the nineteenth century new possibilities opened up for ambitious young women wishing to carve a career in the arts for themselves.

It was initially small private institutions that understood the potential – both financial and artistic – for admitting women into a programme of structured fine arts training. The Académie Julian, founded in 1868 by Rodolphe Julian, a former wrestler, was one of the most prestigious art schools in Paris and included a large studio exclusively for women in 2, rue de Berri, just off the Champs-Elysées, which opened around 1890. Another Parisian school, the Académie Colarossi, also pioneered the inclusion of female students. In contrast, it took longer for the official institutions to acknowledge the need for inclusiveness. Women were banned from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris until 1897. [4]

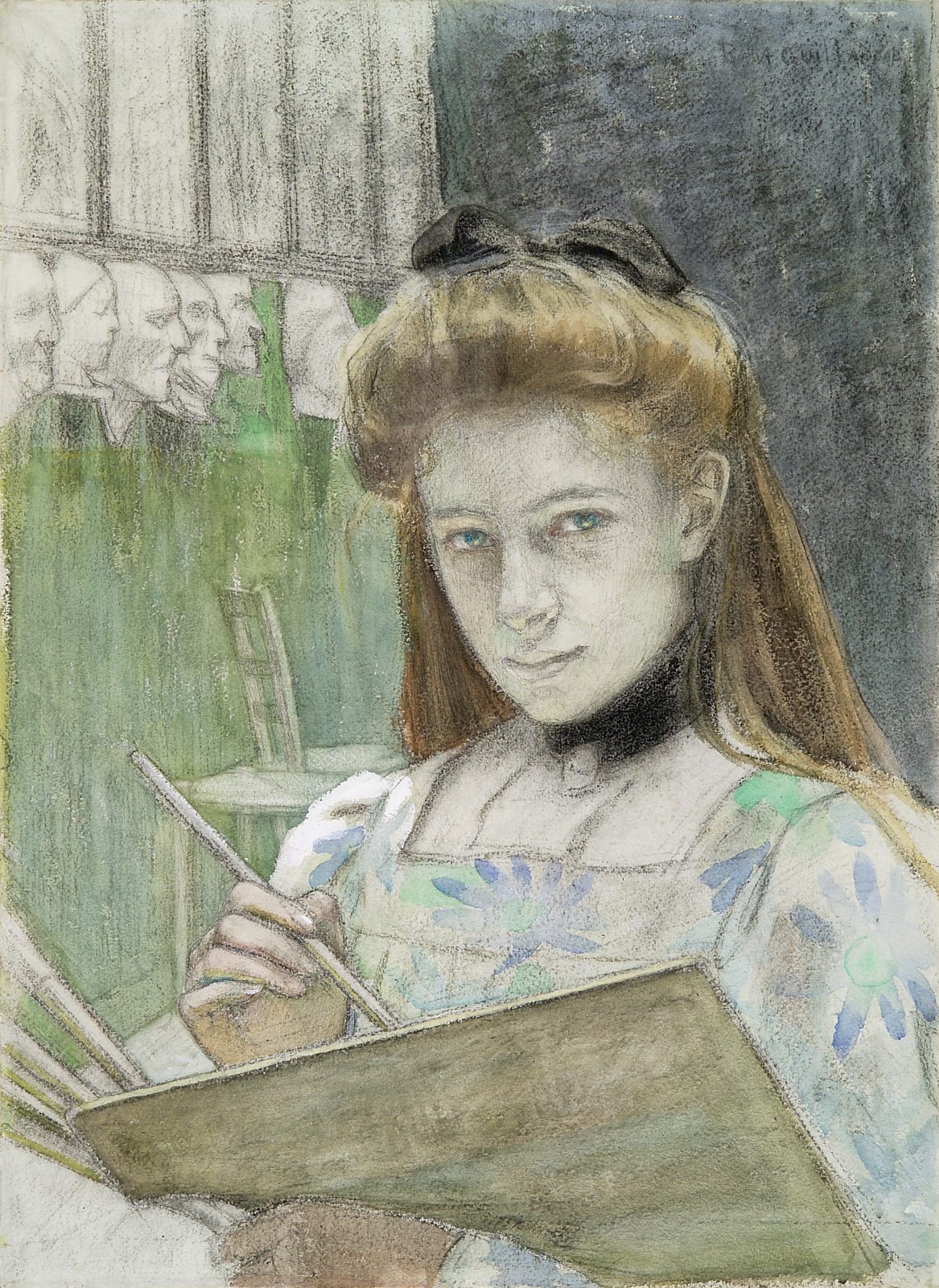

One of the most promising pupils of the Académie Julian was Rose-Marie Guillaume (Tours 1876–circa 1930 Paris), whose masterful watercolour shown here offers an intimate encounter with a female artist in an atelier (fig. 3). It is likely set at the Académie Julian’s rue de Berri studio, where Guillaume trained and later gave lessons. Although this confident drawing could represent a fellow student, the young woman’s assertive gaze suggests it may indeed be a self-portrait. [5]

Notes:

[1] The literature on the subject has increased significantly. For a recent publication see: L. Madeline et al., Women Artists in Paris, 1850–1900 (New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the American Federation of Arts, 2017).

[2] A. Berès (et al.), Francois Bonvin, The Master of the Realist School, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Galerie Berès, and Pittsburgh, The Frick Art Museum, 1999, under cat. no. 19 (as lost).

[3] Two of Sophie Unternährer’s paintings have appeared on the art market, both showing a taste for all’antica subjects and focusing on female figures.

[4] The Royal Academy, London, began admitting women in 1860, but they could not attend life classes there until 1893. See Nancy G. Heller, Women Artists. Works from the National Museum of Women in the Arts (New York, 2000), pp. 60-61.

[5] G. Weisberg, ‘The Women of the Académie Julian: The Power of Professional Emulation’; in idem, and J. R. Becker (eds.), Overcoming All Obstacles. The Women of the Académie Julian, exhibition catalogue, Williamstown, The Sterling and Francine Clark Institute, 1999-2000, pp. 30, 33, fig. 28.

François Bonvin, Sophie Unternährer at her easel, c. 1848, oil on canvas, 24.2 x 18.7 cm, Katrin Bellinger Collection.

François Bonvin, Study for Sophie Unternährer at her easel, c. 1848, black chalk, 23.7 x 15.6 cm, Katrin Bellinger Collection.

Rose-Marie Guillaume, A woman painter in the studio of the Académie Julian, Paris, late 1890s, black chalk, watercolour, gouache, 61 x 44 cm, Katrin Bellinger Collection.